Leap seconds, clock drift, and why your server thinks it is in the future.

As a programmer, you usually treat time as a constant. You call Date.now() or time.time(), get a number, and move on. You assume that if you save a file at 10:00:00, it happened before the file saved at 10:00:01.

But the moment you step into the world of Distributed Systems, you realize that time is actually a lie.

If you have a server in Mumbai and a server in US East 1, they will never truly agree on what time it is. And trying to force them to agree involves some of the weirdest engineering hacks in history.

The Problem with “Now”h2

Here is the fundamental issue: Computers keep time using quartz crystals. These crystals oscillate at a specific frequency. But crystals aren’t perfect. They react to heat, cold, and aging.

This leads to Clock Drift.

Your server’s clock might drift by a few milliseconds every day. That doesn’t sound like much until you realize that in a distributed database, “who wrote this data first?” determines whether a transaction is valid or fraud.

If Server A (fast clock) writes data at real-time 12:00:00 but thinks it’s 12:00:05, and Server B (slow clock) reads it at real-time 12:00:01 but thinks it’s 12:00:00, Server B will think the data traveled back in time.

The Leap Second Panich2

You might think, “Okay, we’ll just sync them with an atomic clock.” But then you run into the physics of the Earth itself.

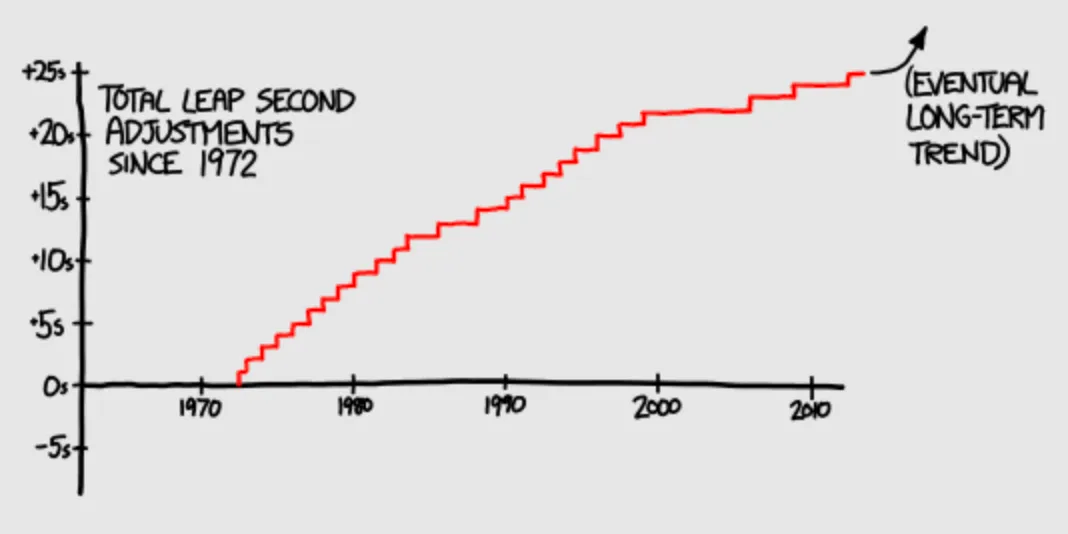

The Earth’s rotation is slowing down. It’s not a perfect 24-hour cycle. To keep our clocks aligned with the sun, scientists occasionally add a Leap Second.

This means that occasionally, the time isn’t 23:59:59 -> 00:00:00.

It goes 23:59:59 -> 23:59:60 -> 00:00:00.

Computers hate this.

In 2012, a leap second was added. The Linux kernel saw 23:59:60, panicked because it didn’t know how to handle a 61-second minute, and livelocked. Reddit, Mozilla, and Linkedin all faced massive outages. It was chaos caused by a single second.

Google’s Solution: Smearing Timeh2

To solve this, Google (and now Amazon/Meta) decided to stop listening to the official time. Instead, they use Leap Smearing.

Instead of adding one second all at once and shocking the CPU, they “smear” that extra second over a 24-hour period. They make their clocks tick slightly slower for a day—microseconds slower per second.

Leap Second Adjustments since 1972

By the end of the day, they have “caught up” with the atomic time without ever forcing the computer to process a 23:59:60 timestamp. It’s a brilliant, slightly terrifying hack where we intentionally slow down time to keep servers happy.

NTP is Black Magich2

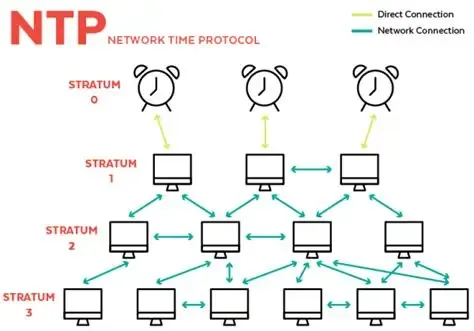

To keep servers in sync, we use NTP (Network Time Protocol).

You might think NTP just queries a server and asks “What time is it?” But that doesn’t work. If the request takes 50ms to travel to the server and back, the time is already old by the time you get it.

NTP does heavy statistical analysis. It pings multiple servers, calculates the round-trip delay, estimates the asymmetry of the network path, throws away outliers, and gently nudges your clock forward or backward (slewing) rather than jumping it, so it doesn’t break running processes.

It relies on a hierarchy called Strata.

- Stratum 0: Atomic clocks / GPS.

- Stratum 1: Computers directly connected to Stratum 0.

- Stratum 2: Computers connected to Stratum 1 (this is likely your server).

When Milliseconds Are Too Slow (The Stock Market)h2

NTP gets you within a few milliseconds of accuracy. For 99% of apps, that’s fine.

But for High-Frequency Trading (HFT), a millisecond is an eternity.

If I buy Tata Motors stock and you buy Tata Motors stock, and our orders hit the exchange 0.001 seconds apart, the price might have changed. Fairness requires microsecond or even nanosecond precision.

NTP cannot handle this. The software stack (Linux kernel, interrupts) introduces too much variable delay (jitter).

So, stock exchanges and HFT firms use PTP (Precision Time Protocol).

PTP uses hardware timestamps. The Network Interface Card (NIC) stamps the time the exact instant the packet leaves the physical wire, bypassing the Operating System entirely.

They also don’t rely on the internet for time. If you look at the roof of BSE or major data centers, you’ll see GPS antennas. These provide highly accurate time directly from satellites, since internet-based time sources have variable delays and can’t match the precision and stability of GPS

The Takeaway for Programmersh2

- Never use local time on the server. Always use UTC. Local time has daylight savings, which creates gaps where time either jumps forward or repeats itself.

- Time is not a number line. In distributed systems, it’s a “happened-before” relationship (look up Lamport Timestamps if you want another rabbit hole).

- Assume your clock is wrong. If your code relies on the system clock being perfectly accurate to prevent data corruption, your design is flawed.

Time isn’t just a measurement; in computing, it’s a consensus problem. And as we’ve seen, getting computers to agree on anything is never easy.

Comments